I was having a discussion with my supervisor (as one is prone to do at university), and the discussion of agency, as inevitably happens in games discussion came up, but it came up with a twist in regards to

Life is Strange.

Although not made explicit

Life is Strange is one of those games which lets the player run along with their choices, or the twoing and froing that can occur within a videogame. Much like the rewind power in

Prince of Persia: Sands of Time, Life is Strange uses time mechanics to go and provide players with an in-game mechanic. Although while

PoP uses it in conjunction with it's in-fighting, to provide that perfect fight,

Life is Strange does the same thing, but instead of it dictating whether or not a sword thrust made it to your belly, it instead allows players more room to see the consequences of their actions, an in-game version of reloading and saving their game.

Although the game manages to game this system (in that decisions don't have their long term consequences revealed until an episode or two later), it does raise an interesting application for allowing audiences to play with choice. Although in other video games (Telltale Games in particular stand out), consequences of choices may not be abundantly clear prior to a player making them (indicating if it were the sequence of events), most players choose to make a decision, before reloading and choosing another option - indeed if the post game percentage of player is an indicator, players post completing a game will replay the game to have the "best" choice made available.

Life is Strange manages to give players enough of ownership in their choices in order to see it through - but furthermore, the game makes staying with these choices crucially part of the narrative.

The plot points build upon set narrative pieces, as well as specific actions done by the player enough so that the player's effect is felt and then reflected in the plot on screen - or at least enough to grab the player's attention (see illusionary agency). Players get a chance to see all the possible choices in each section before moving on (with the rewind time function) and as a result of that their choices have a bigger impact. Purely because the game has given it's audience more of a moment to settle in with their choice, to own it instead of brushing ahead with the immediate reactions to it. Well, that's at least one part of it, the other would be the constant references back to the decisions made, and the internal dialogue that plays out in terms of referencing. This includes not only the immediate reaction, but also later consequences that occur two or three episodes later. Decisions have a staying power that seems to make a big impact in the world - that's not to mention the great use of supporting characters who both react to your actions, but also have their own lives that you can glimpse into. Although not necessary for the plot (at least in some cases), it definitely makes for a much more liveable world that has the scope for exploration. All this stuff is what I'd like to plot for my thesis, or failing that start talking about in papers (something about metalepsis).

Indeed in the latest episode

Chaos Theory, in the conclusion, the effects of trying to alter too much are shown (addressing some of the concerns of the game's audience), resulting in a bizarro alternative world where there's a limited frame of reference to any of the events in the previous episodes. Here the effects of a conscientious player trying for the "best game," can be revealed, as like Max their meddling can break the world. Although the player's power isn't omnipotent, it is considerable enough to break the world. And in the same way that Max breaks her world through altering something, considered to be unalterable, the game gives players a hint about their rewinding/saving-loading power, it's a powerful thing, but it can be abused. This is probably reading way too much into the video game, but it is an interesting message that ties in well with the mechanics of the game, as well as the game narrative - it's a really interesting piece of work.

Further with this choice of player choice, is the option to read the world and the choices present in a Nichomachean Ethics/Virtue Ethics, kind of way. In that, for the game and the player, keeping a consistent idea of a character, that is to say making sure not to deviate outside of what the character might do, the most "true," game can be had by the player. This is somewhat helped by the themes within the story of trying to consistently change fate, in line with what the main character Max believes to be best - I mean most people would try to do just that given the power to rewind time. However it really does seem that in being, at the very least consistent (as is the case for most RPG games) seems to be the most rewarding in-game as it provides a much more logical narrative than one that jumps around with character development. Though that being said, most games/narratives do rely on their main character having a consistent character which leads to personal discovery, rather than an ambivalent sense of self, or virtue. In either case keeping consistent seems to be the key to having a good narrative, or narrative experience.

Anyhow, that's my 10 cents worth of blogging for today, though I will say that the game is an interesting one to study, as it provides a lot of different mechanics and narratives in interesting combinations. Including disempowering it's players at a crucial junction - raising the dramatic stakes of the narrative, through the loss of controls (literally and figuratively). Though that's a discussion for another time.

Other thoughts would be to draw parallels from

Life is Strange, and having a comparison with the

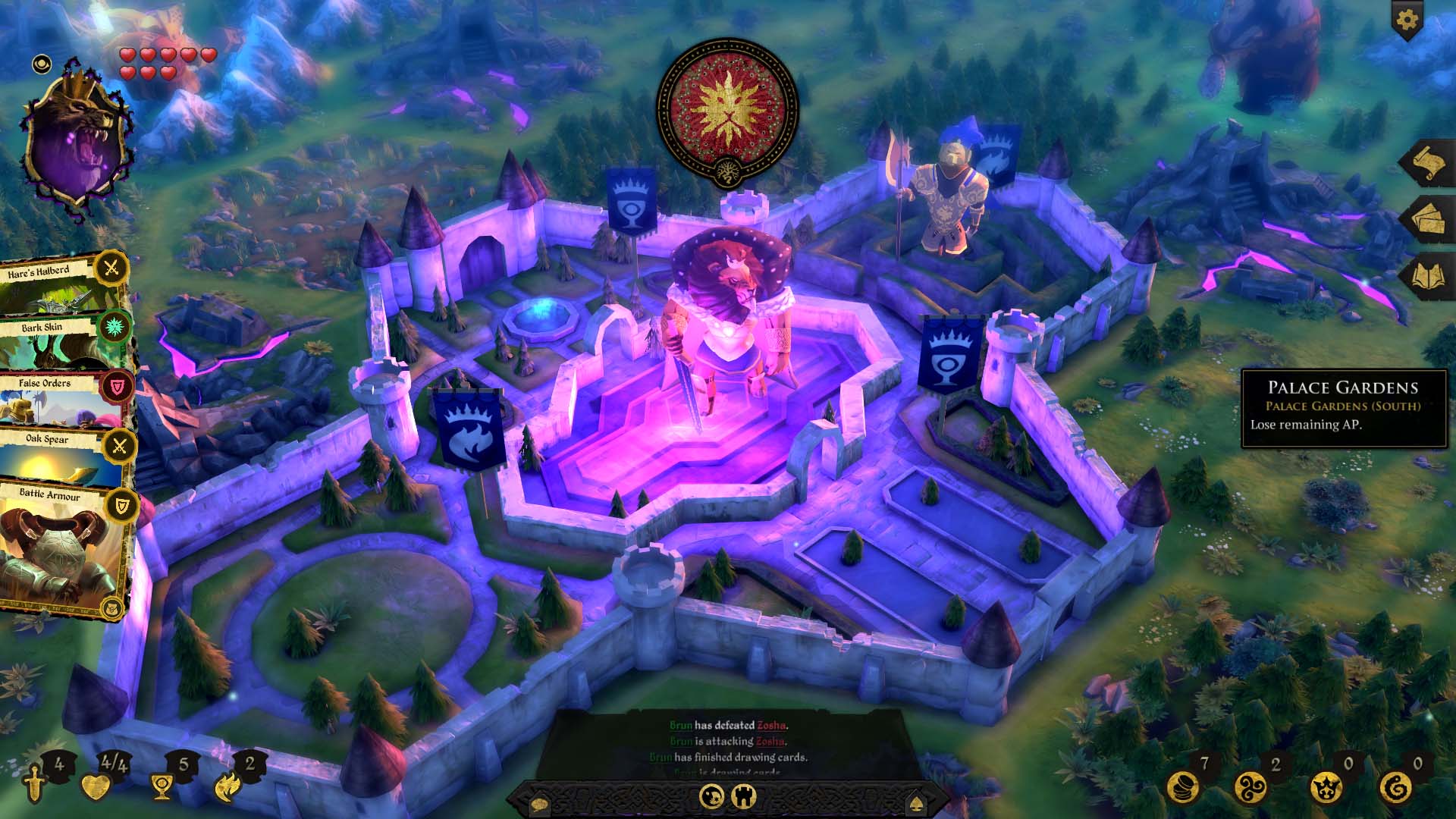

Witcher 3 of the characterisation of the world, or the way that characters interact with each other (as opposed of solely with the player). There's some other games that do this well (I think

Psychonaughts is up there), but these are the most recent that work with this notion of having other characters progressing in the same world as the player (or at least giving a good simulation of it). At least in a storytelling game.