Wary Ludologist Timid Writer

Monday, 18 June 2018

Into the Breach and FTL

Into the Breach is a turn based tactics game from the creators of FTL, Subset Games. These two games provide two very interesting approaches to the notion of story within a rogue-like. FTL presents its story through the random events presented en-route to defeating an enemy flagship, whereas Into the Breach, provides narrative through the introduction of the game world, and the meta-narrative that surrounds it.

The story in FTL is light, the rogue like nature of the game, and the variety of races that the player can meet meant that the variety of 'side quests' for lack of a better term were varied along a series of chances, and player action. From the Crystaline entity who can eventually wake up and take you through to another dimension, to boarding a ship of mantis to overthrow an enemy captain. All of these small randomised and difficult tasks reward the player with, if successful new ways to play FTL through the acquisition of new crew and ships.

For Into the Breach such variation does not occur in game, instead the possibility for variation is presented readily in the introduction of the game with the presentation of time travel, different mechs and pilots. All the necessary information is presented at the start of the game - that pilots can return to a different timeline to begin their battle anew (akin to Edge of Tomorrow), ensuring that players are given enough variation, and stories they can create through these already established blocks of gameplay - that of mechs, pilots and time travel mechanics.

Where the two games differ is in the presentation of these narrative events, for FTL these narrative sections rely on a mixture of luck, skill and placement by the game to occur, whereas with Into the Breach the player is readily given an overview of all possible pathways to the mech or pilot they wish to have. Unfortunately this lack of narrative events (more so cause and effect on the state of the palyer) is not present in Into the Breach, the gamepaly is oddly divorced from narrative events, short of losing or succeeding there is little variance in how events progress and how players can effect each of the 4 islands. For FTL the player is given characters and progression as they proceed to encounter these side quests. There is choice of customisability, in different areas to protect from the Vek, and in the randomised pilots players may chance upon in each area - however all of these features were present in FTL in addition to the side quest opportunities.

In a way the presentation can be summed up as having all the information readily laid out, like with Mario or Tetris there is not much room for variation in the overall thematics of the game. Into the Breach is no different it readily provides this information so that players can see the permutations of gameplay more readily. In FTL the randomised secondary quests changed some thematic elements of the game, giving the gameplay/story extra depth as well as forcing the player to consider other elements beyond their ability to progress to the next level. Although hard to replicate (these events were sporadic and randomised) it meant that FTL appeared to have more depth and variety in the actions that the player could take, and also variety in actions that the game could take. It's the old rick of not showing everything to the audience so that they assume that the game is larger/more complex than it is - not that FTL is not complex, more so it hides a lot of it's features so that players can discover them over the course of multiple game sessions.

Here we have a good dichotomy to think about when constructing Roguelike games/ narrative content for consistent gameplay occurences.

Saturday, 10 March 2018

Master's Thesis finished

It seems a strange thing to say after a period of three and a half years of studying and writing, but as of this week Thursday I'll have graduated with a Master's of Arts by research. Closing the first chapter of my foray into research and leaving me a wake of mental strain and exhaustion. So I have not pushed as hard as I once did with writing papers or tutoring, or push myself to do a PhD (which I was nearly in the process of applying for in October). No instead I've given myself over to work and am enjoying the 9-5 cycle of employment.

That is just the current state of things devoid of speculation of games, reviews or upcoming projects. Over the next few weeks I'll try and return to regular postings about new games that come out, starting with Into the Breach (by Subset games makers of FTL), with some musings about narrative based games, some insight into playing Monster Hunter, and the cooperative pleasures of Vermintide II.

For now enjoy a link to the finished thesis: http://hdl.handle.net/1959.3/442127

That is just the current state of things devoid of speculation of games, reviews or upcoming projects. Over the next few weeks I'll try and return to regular postings about new games that come out, starting with Into the Breach (by Subset games makers of FTL), with some musings about narrative based games, some insight into playing Monster Hunter, and the cooperative pleasures of Vermintide II.

For now enjoy a link to the finished thesis: http://hdl.handle.net/1959.3/442127

Saturday, 4 November 2017

Life is Strange: Before the Storm - Quantifiable choice

Life is Strange: Before the Storm, sits at an interesting cross section of interesting theme and gameplay mechanics, but compared to the original Life is Strange it falls a bit flat in my eyes. This entry largely compares Life is Strange to it's prequel Before the Storm to see how these games differ in their approaches to teen interactive drama, by focusing on both the positioning of the narrative, and the gameplay mechanics used to emphasise the choices being made. I'll take care not to reveal spoilers about the game, but be warned going forward that details of how the game's choices play out, will the focus of this entry. So you've been warned.

On the one hand Before the Storm attempts and succeeds at doing it's own thing by having Chloe Price as the main character, and having her have her own 'backtalk' mechanic. On the other hand the focus on Chloe and Arcadia bay, before Max's arrival limits the story to a predefined point and knowable point for audiences: Chloe eventually selling drugs to Nathan Prescott at the start of Life is Strange: Episode 1. As such there doesn't seem to be a lot of wriggle room as to how the choices in the prequel can affect the next game. Simply because of the prequel status of Before the Storm there's a lot of predetermined events that limit the agency of characters and events. This progression is similar to the prequel's in Star Wars where the importance of these prequel events is to contextualise what occurs later on in the series, and to give reasons as to why Chloe, Rachel, Arcadia Bay are the way that they are by the new season. However with this in mind there are a lot of characters and events from Before the Storm that are mysteriously forgotten by the start of Life is Strange. It's a mistake that appears commonly in the post development of prequels with a lot of characters and events left unexplained in the 'main event' of the series. Do these characters all suddenly leave town? Or is there an area which developers won't explore, providing an inconsistency that fans can provide their own answers for?

|

| Where does Drew North go? Or alternatively where do the cast of Life is Strange appear from? |

|

| Oxenfree also a fun teen interactive drama. |

The most detailed path so far for Life is Strange: Beyond the Storm appears to be the variety of action that can be taken after stealing some money. Most of this is related to whether or not Chloe buys drugs, supports her mother, or pay back her debts. Another variation appears to be how Rachel responds to Chloe, and builds from either a romantic or platonic friendship, however this builds on the previous responses of Chloe to inform how Rachel will react, and doesn't so much alter a variety of results, but aggregate to one of two states (will Rachel be receptive to Chloe's advances, rather than will different results occur out of this state). In this the range of alterable content appears to be less that Life is Strange's original gameplay, in that the most complex changes are inconsequential to the progression of Chloe and Rachel's relationship, and furthermore do not appear to 'stack' as the player progresses through the game. To provide a yardstick for comparison, there's no counterpart to Kate and Max's relationship in Beyond the Storm.

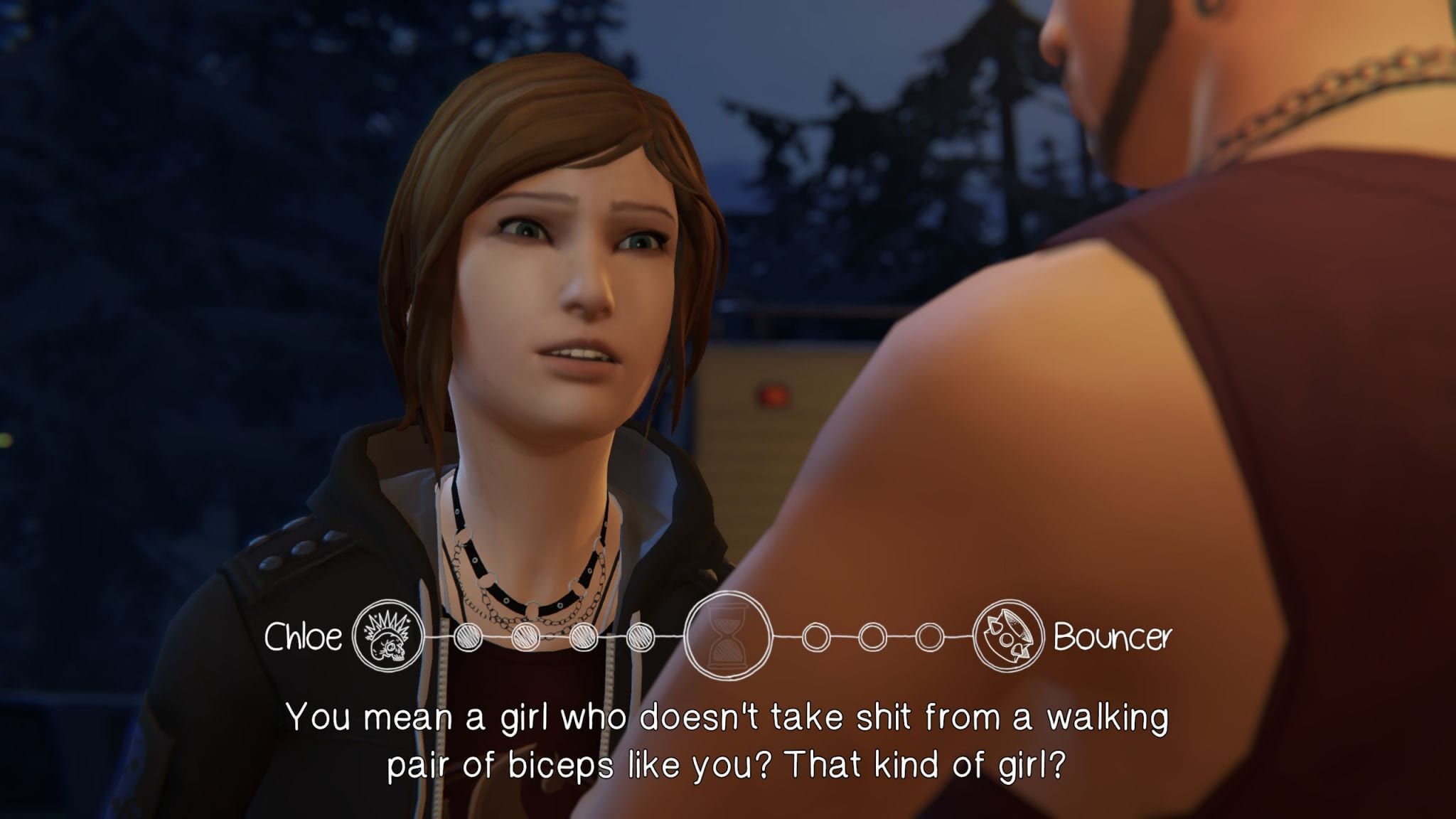

The other aspect of this perceived 'lack of choice' is that the game doesn't readily announce when a choice has been made by the player (aside from the auto-save icon). In Life is Strange, such situations would be readily identified by Max and the alternative action was readily available to be explored through the time rewind ability. Even when these actions were hidden or made obtuse, the player still had the opportunity to play around with events and see what the immediate consequences of their actions were. For Chloe no such power exists, and with that no awareness that things can turn out differently.

Chloe's rash behavior is explained by the death of her father; however the cycle of self-destruction (alienation of friends, family, and abandonment of her education), seems at odds with the people in Chloe's life - the only negative people who have the power to affect her are Principal Wells and Joyce's boyfriend David (who are well outside Chloe's circle of friends and family). Based on the support group Chloe already has, it seems as though her mood could only improve instead of becoming self destructive. Similarly Chloe's actions don't seem to be hurling her into anything dangerous or unsavory (i.e. she goes to school and sees a band that she likes), yet she these actions are seen as grounds enough to be punished (suspended/expelled from school). To sum up the manner in which you can behave as Chloe does not seem to reflect how the community should or does react. There's an argument to be made for how bad Chloe is perceived by the community, but many of the reactions provided through a 'good' playthrough appear to be over the top. If anything the game doesn't accurately portrait Chloe as being accurately reacted to, or acting out in an unexpected manner, if anything there's a disconnect between the player's ability to play Chloe in a 'good' manner and the reactions of the game.

|

| To boot some of the backtalk feels a bit too awkward for a game that relies heavily on dialogue. |

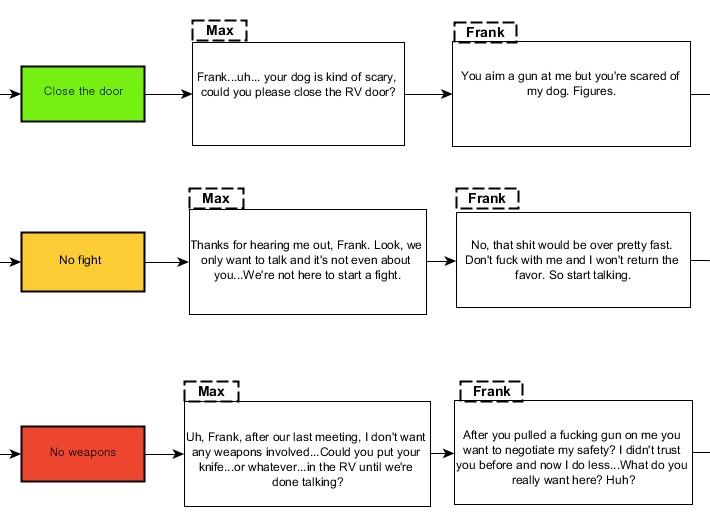

Taking another examination of these choices, for the player the ability to know that there is another choice in many matters occurs from replaying the game a couple of times (which may or may not reward players for their actions), looking through the end of game percentage of choices, or searching online for different consequences that occurred in other player's playthroughs. From these roadmaps, hints and discussions players can discover alternative responses to their actions, as opposed to playing through Before the Storm multiple times to see what actions can change. Life is Strange also made use of long term effects for Max's actions (so players wouldn't be able to change these events immediately), yet balanced this with having an immediate response/consequence as well as a later consequence to consider, which would build up on other choices. These results too were hidden for players, but due to the design of immediate consequences, and a range of responses, the exploration felt as though a different series of events was happening, instead of the same event with a different inflection given. As such the choices provided in Before the Storm do not feel as intuitive due to the lack of rewind mechanics and the limited range of responses provided in comparison to Life is Strange (see the fan site).

|

| Section taken from Venture Beat |

Tuesday, 17 October 2017

Where's my Content: finding the DLC

This post is largely prompted by the Obsidian/Paradox survey about DLC and what's an apt distribution strategy for DLC and what price points are worth considering for consumers. I took a different approach to analysing the DLC situation with Tyranny.

Downloadable content or DLC, is often provided readily available in games and promotes a number of ways of accessing it for a player, however this is not always the case in a number of games. For myself I am talking about Tyranny and Stellaris which provide increased functionality in their games (equivalent to Civilization expansions). However they do not provide this content to the player immediately. Instead the content is spread out across each gameplay cycle (Act I, II and III in Tyranny) based upon the player's progress or obstructed by the need to complete different conditions for the DLC content to come into effect (such as Stellaris' DLC Synthetic Dawn for ). For the purposes of making a deeper system this makes the game more mysterious and complicated, however for players familiar with the game series the need to search through content already traversed, and as such the game becomes one where finding the content is the first puzzle to undertake. However before delving into the DLC of Tyranny and Stellaris a quick reflection on other videogames noted for their DLC will help situate the discussion.

Comparatively to Paradox Interactive's approach DLC from other companies appears to be much more immediate in it's presentation to the player. Focusing on XCOM 2 or The Witcher 3, both games highlight which version of their game that the players is playing is part of. For XCOM 2 the player is able to on the launch screen (just before the game starts, a preface for news, or changing options) to choose which version of the videogame to play, following this there is a different introduction video, a different menu screen, the loading screens, and a different introduction to the game which includes highlighting new mechanics and content.

At each of these stages XCOM 2 identifies that it is a different experience, with different content and a constant presence of title to remind players of the new content.For The Witcher 3 such new content is left in the in-game window as well as the launcher for the videogame.

Interestingly The Witcher 3 allows for players to access this new content immediately, separately from the main quest of The Witcher 3. To this extent the manner in which the DLC is introduced is one which players can access from all or most styles of play. In this way players can combine their experiences of The Witcher 3 with the DLC or jump straight into it without having to complete any milestones besides purchasing the game. It should be noted that the scores for these DLCs were well received as well as numerous.

For Tyranny the DLC is present in the in-game menu (on the top right of the screen) and in some of the start options (allowing for the DLC content) however there is not a lot of indicators for the addition of this new content.

For Tales of the Tiers the presence of in-game event pop-ups on the world map (an hour or two into the game) reveals the addition of the DLC content. For Bastard's Wound the additional content is only available after the first act and after the completion of Leviathan's Crossing, from there players are contacted by a messenger and can go to the new content alongside their regular completion of the main quest. Other than this there is no new content or indication of new content for the player in their playthrough of Tyranny, this means that while there is new content it is weaved into the pre-existing game, and not treated as a unique separate section (like in XCOM 2 or The Witcher 3).

For Stellaris (which is probably the most different game from the others we've examined) the presentation of DLC is done so through the launch screen, the in-game menu, and in the loading screens. The content is a mixture of discreet units (based in the DLC content) and the normal updates to the game (where it is constantly being updated), as such players who purchase the DLC are treated to a combination of both discrete new gameplay (the ability to build super structures Utopia, play as synthetics Synthetic Dawn, or battle space creatures Leviathan), and general improvements to the overall game (the manner in which sectors, governors, unity and other aspects have changed).

In this manner players are able to see both what their purchases provide, and are able to enjoy the benefits of constant patching. There is a similar barrier in Stellaris to content the way Tyranny presents DLC, in that certain states (completing different requirements) are necessary to gain access to different sections of the DLC - for Synthetic Dawn players must be a synthetic race to gain access to that content, for Utopia players need to progress to a certain technological stage, and for Leviathan players must find these space creatures to be able to fight them. The design of the game and the manner in which Paradox Interactive release patch notes and additions to Stellaris supports the style of DLC integration of being a distinct unit but also one that builds upon the regular updates to the game.

For Tyranny such integration of DLC seems unconventional alongside the type of game (RPG) that it is, to accompany this the incremental nature of some of the DLC that is extra random events to occur seems like a general improvement to the game (ala a patch) rather than a discreet unit. Furthermore to access this aspect of the game the player relies on a degree of randomisation, or rather a deep understanding of the game system to force these events to happen. As opposed to the DLC for XCOM 2 and The Witcher 3 which present new content readily, the barrier to entry in Tyranny is high for the content to be enjoyed.

Although there are certainly great success stories with the application of DLC within various videogames, for Tyranny the application of DLC doesn't sit well within pre-established RPG conventions (from The Witcher 3: The Wild Hunt) or within the realm of Paradox Interactive's other products.

Downloadable content or DLC, is often provided readily available in games and promotes a number of ways of accessing it for a player, however this is not always the case in a number of games. For myself I am talking about Tyranny and Stellaris which provide increased functionality in their games (equivalent to Civilization expansions). However they do not provide this content to the player immediately. Instead the content is spread out across each gameplay cycle (Act I, II and III in Tyranny) based upon the player's progress or obstructed by the need to complete different conditions for the DLC content to come into effect (such as Stellaris' DLC Synthetic Dawn for ). For the purposes of making a deeper system this makes the game more mysterious and complicated, however for players familiar with the game series the need to search through content already traversed, and as such the game becomes one where finding the content is the first puzzle to undertake. However before delving into the DLC of Tyranny and Stellaris a quick reflection on other videogames noted for their DLC will help situate the discussion.

|

| Fallout 4 DLC |

Comparatively to Paradox Interactive's approach DLC from other companies appears to be much more immediate in it's presentation to the player. Focusing on XCOM 2 or The Witcher 3, both games highlight which version of their game that the players is playing is part of. For XCOM 2 the player is able to on the launch screen (just before the game starts, a preface for news, or changing options) to choose which version of the videogame to play, following this there is a different introduction video, a different menu screen, the loading screens, and a different introduction to the game which includes highlighting new mechanics and content.

|

| XCOM 2 War of the Chosen Launch screen. |

|

| DLC Loading Screen for XCOM 2 War of the Chosen. |

|

| New Game appears differently for the player, readily identifying new characters for the player to use in their campaign. |

|

| Launcher for Witcher 3 |

|

| Game Menu for Witcher 3. |

|

| Selection for DLC content. |

For Tyranny the DLC is present in the in-game menu (on the top right of the screen) and in some of the start options (allowing for the DLC content) however there is not a lot of indicators for the addition of this new content.

|

| Tyranny Game Menu |

For Stellaris (which is probably the most different game from the others we've examined) the presentation of DLC is done so through the launch screen, the in-game menu, and in the loading screens. The content is a mixture of discreet units (based in the DLC content) and the normal updates to the game (where it is constantly being updated), as such players who purchase the DLC are treated to a combination of both discrete new gameplay (the ability to build super structures Utopia, play as synthetics Synthetic Dawn, or battle space creatures Leviathan), and general improvements to the overall game (the manner in which sectors, governors, unity and other aspects have changed).

|

| Loading screen for Utopia DLC |

For Tyranny such integration of DLC seems unconventional alongside the type of game (RPG) that it is, to accompany this the incremental nature of some of the DLC that is extra random events to occur seems like a general improvement to the game (ala a patch) rather than a discreet unit. Furthermore to access this aspect of the game the player relies on a degree of randomisation, or rather a deep understanding of the game system to force these events to happen. As opposed to the DLC for XCOM 2 and The Witcher 3 which present new content readily, the barrier to entry in Tyranny is high for the content to be enjoyed.

Although there are certainly great success stories with the application of DLC within various videogames, for Tyranny the application of DLC doesn't sit well within pre-established RPG conventions (from The Witcher 3: The Wild Hunt) or within the realm of Paradox Interactive's other products.

Saturday, 30 September 2017

Critical Eye: Lara Croft Tomb Raider

There’s a frequent argument for the improvements, the

progression of female representation in videogames, from Tomb Raider which is praised for a more realistic representation of

the female body, to the improvements of female representation (as lead and

playable characters) within Gone Home,

Her Story and Life is Strange.

Yet even in the supposedly progressive games the interactions of these female

protagonists are still constrained by gender norms that still restrict these

women to be supportive rather than having a spotlight solely on them.

For today we’ll be focusing on Tomb Raider to broach some of these notions of advertised

‘progressiveness’ against that of what’s actually in the game.

The biggest indication for equality as promoted by the

developers and reviewers was the more realistic body image. Although certainly

a nod to ‘realism,’ especially when contrasted with previous Tomb Raider games a more realistic

looking character can still be sexually

objectified, and does not make a game inherently progressive. In some ways

it restricts the ability of objectification in the game but this offers no

counter argument to the male gaze that pervades Tomb Raider.

By male gaze the perspective of the camera instantly

provides a perspective of Lara Crofts sexuality. In the midst of Lara’s most

harrowing scenes, from frowning from falling, from being impaled, the viewer is

invited to see Lara as primarily a sexual object and not someone in fear of

their life. The added extended death scenes further promote such exploitation

of Lara’s pain and anguish as desirable for the player in that each type of

death is specifically animated for the gratification of the player. There is

added context in the suffering of Lara, without failing a task the player has

no means of accessing it, and so is encouraged to in the process of a game, to fail

to see these deaths.

The above video showcases a particularly nasty case of in-game

failure and strongly suggests further sexual violence against Lara. The game

doesn’t address this scene at all which makes its inclusion and later lack of

commentary one that doesn’t progress any discussion of sexual violence, and if

anything normalises apathy towards it. This scene aside there are plenty of

others which are gory for the sake of gore and visual spectacle rather than for

character progression or storytelling techniques.

Such added content can be explained away as padding or

necessary for such a game (in the words of Ron Rosenburg executive producer of

the game ‘you want to protect her,’). These deaths are necessary to emphasise

the death that surrounds Lara on all sides. However, in providing such graphic

deaths and attention to detail in these scenes the emphasis seems to establish

that Lara’s suffering is meant to be entertaining for the audience. The inclusion of these graphic deaths does

more to take away from Lara Croft’s independence and promotes that Lara

naturally cannot take care of herself.

Moving away from such discussion of deaths and the

accompanying male gaze on Lara the next area to examine is how well the

narrative represents Lara Croft, and other female characters as autonomous

beings without succumbing to gender performativity (mainly being support roles).

Using the Bechdel test

Tomb Raider escapes from being labelled solely a masculine tale since the

female characters do talk about something else besides men. However, looking at

the narrative many of the movers and shakers of the story rely on the presence

of men. That’s not to say that there’s no need for men in the story, rather the

narrative relies on normative conventions that have men as the primary force.

So,

let’s review:

- Lara Croft explores the isle of Yamatai as it was one of the last things Lara's father wished her to discover. Although this provides a good motivation for Lara to go to Yamatai island, it might have been more autonomous to have Lara exploring due to her own interests rather than accomplishing her dead father’s will.

- Lara Croft is saved a number of times (sinking ship, attack by cultists, frostbite and jumping on helicopters) by her father figure Captain Roth. Roth is ultimately killed because he saves Lara too many times. Having Lara saved once may have been enough, but three times makes Lara seem more than inept in the wilderness.

- Lara Croft’s villains are primarily bad dudes (Mathias, and Whitman). The big bad is revealed to be a female spirit, but she is largely characterised as a big ol’ ghost rather than a character with any depth. Having Lara’s enemies as something a bit more diverse than opiniated white guys, may be a step in the right direction.

- Lara Croft’s best friend, Sam, is found by the end of the game to be a vessel for an empress (and so de facto royalty). Sam needs to be rescued to keep her being possessed by undead royalty by Lara – Sam otherwise serves no purpose other than a motivation to keep going further. If Sam provided some gameplay value (such as Alex in Half Life 2 or Elizabeth in Bioshock: Infinite) then her role would be much stronger.

- Lara Croft rewards one of her companions, Alex the IT guy, with a kiss for heroically failing to grab tools for the other members of the crew. Alex seems to be redundant in the game and in the narrative as someone who shouldn’t at all be on a trip to explore a forgotten island. Removing this character and scene completely would improve the game immensely, or alternatively apply Alex with a bit more character than IT guy who fails to do one job.

The only other female character beside Lara and Sam is

Joslin Reyes who, provides no gameplay help, and offer only negativity to any

plans of escape or survival for the group. Only at the end does she change her

mind based on the urging of the other (male) members of the crew and helps Lara

to go rescue Sam. Also, the game

highlights Joslin’s femininity with the fact that she is a single mother.

Now all of these points can be argued as pointing Lara to

becoming self-sufficient and turning into the rugged and independent woman that

she appears to be in other Lara Croft games. But such claims appear to do more

to hide weak characterisations of women, and to defend the game from criticism.

From asking such questions and analysing Lara Croft as something which can be

improved the game and representations of women can be made much better.

Comparing these characterisations against that of the

previous Crystal Dynamics game Tomb

Raider Underworld, Lara Croft can be seen as more self sufficient.

In the above video Lara is seen to be independent to the

extent that when her friend Zip refuses to drop his weapon (under a

misapprehension about Lara) Lara calmly shoots him in the leg to prevent the

situation from escalating. Although a bit extreme (to say the least) it’s a pragmatic

way of dealing with the problem at hand. Through this action Lara Croft

identifies herself character that deals with no nonsense to resolve problems.

Later her hacker best buddy Alister Fletcher, dies to Lara’s

evil Doppelganger, and sure she morns him, but she doesn’t give him a kiss ala

2013’s Tomb Raider. She ruminates

about his fate and resolves to figure out what’s happening with her

doppelganger. Also, not that it should need mentioning having an IT guy at

Croft manor makes a lot more sense than in the middle of the jungle. The added

kick arse ability to shoot willy nilly at everything and not have extended

death scenes for failing some quick time events also makes Underworld empowering of Lara – she’s supposed to win, there’s no

reward for death.

From this comparison it already seems that Underworld portrays Lara in a much

stronger light than in the Tomb Raider of

2013. Rise of the Tomb Raider 2015 is

a somewhat better game but does not reach the same levels of independence and

kick arse-ness that was displayed in Underworld.

All of this is not to say that there are not female

representations in games, especially with the recent release of Uncharted: The Lost Legacy, more so the

point is that even within videogames that are supposedly progressive there is

more that can be done to both improve the narrative and gameplay, alongside the

representation of women.

Tuesday, 12 September 2017

Horzon: Zero Dawn

Horizon: Zero Dawn while widely praised, is not an open world action-adventure game that I enjoy. That being said generally action-adventure games rarely get a glowing review from myself, such as The Last of Us or the Uncharted videogames. However in the case of Horizon: Zero Dawn my lack of enjoyment has less to do with the genre and more to do with the implementation of the open world elements to the player's actions. Before going through the elements which were not enjoyable, Horizon: Zero Dawn should be praised for the aspects that it did well.

- Localised damage for each enemy - this gameplay element was seen largely with the robotic enemies, allowing for an identification of the various subsystems of the robot which you the player could disrupt. Furthermore the added layer of different elemental effects that could be used against each of these subsystems allowed for variation in the combat. E.g. removing armour, shocking, freezing or burning these enemies.

- Combat mechanics - when the combat flowed together well in a combination of jumping, sliding and dodging the fighting felt exhilirating. However this did become tiring when attacking large groups of enemies as a one woman army.

- AI interaction (robots and NPC humans) - this is something that I've only really noticed in Bioshock, Alien: Isolation and more recently Fallout 4. Enemies would attack each other outside of the player's own involvement, which adds to the sense that the world is alive.

- The story - the story deserves a special mention as the creation of the world and the player-character's place in it is well thought out and established. This makes for an engaging narrative for much of the game and propells the player forward (myself included) to discover more about the past and about their character Aloy. Discovery of how events came to be, or the history of gameworlds can be seen in Destiny, Fallout and other futuristic or alternative history videogames. I guess for a lot of these videogames the progression from a set point to a future one is entrancing for players, or at the very least myself.

- Graphically impressive - the graphics are not really a gameplay feature, but consistently spectacular visuals did keep me around a lot longer than I would have with other games.

Beyond these aspects the rest of Horizon: Zero Dawn were enjoyable but not particularly well done. The open world (Far Cry 4, Mafia III), the bow and arrow mechanics (Zelda, Tomb Raider), the climbing (Assassin's Creed, Mirror's Edge) and collect-a-thons (nearly) are all present in other action-adventure games, and in a better state than what you would find in Horizon. These comparisons can be made readily; however what I will focus on is the way in which Horizon: Zero Dawn uses its open world in combination with the actions of the player. By this I mean whenever a certain task is completed by the player, such as a side mission, there's a correspondence in the game world. Such action can usually be seen on the world map and is noted by the characters of the videogame.

To use Mafia III as an example. Completing a side mission or main mission would clear out opposition from part of the game world. However once done the player would then choose which of their subordinates would gain control over an area of land.

This action by the player enabled a response from the game including a visual signifier of the player's gang control on the in-game map, a particular bonus from their subordinate(depending on the subordinate used), and a change to the narrative depending on if the player favoured one subordinate over the others.

Horizon: Zero Dawn employs none of this reactivity during its play, leaving the player's actions in each area largely unnoticed by the game. As a result the progression of the player-character through the game is only really marked through their progress through the main quest. The fact that the player has removed all corrupted zones or bandit camps from the game world is not reflected in other character's responses let alone in a change to the overall narrative.

There are some reaction present in Horizon: Zero Dawn for the players actions, however these are not as prevalent as Mafia III. In completing some of the side quests the player is able to have more allies in a battle towards the end of game, however this appears to be the extent to which there is variation in how the game can be completed.

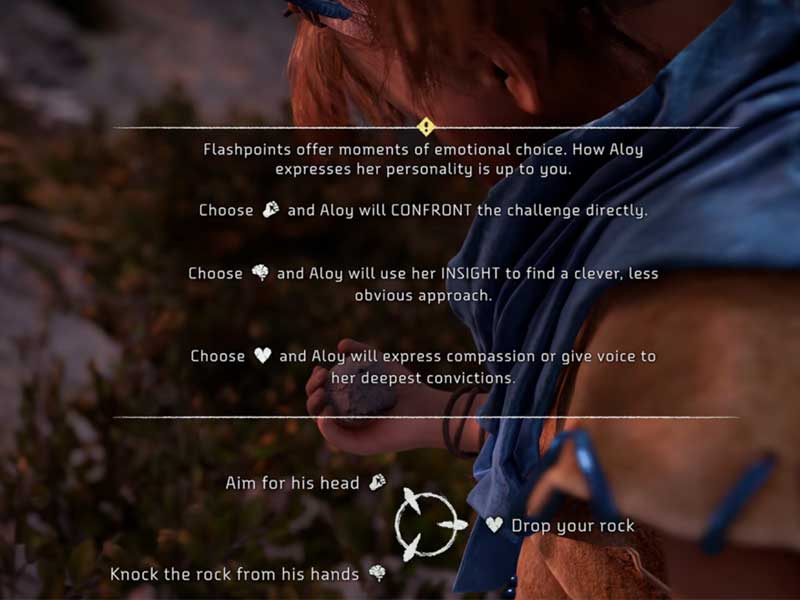

Further, Aloy can have different dialogue and reactions based on the player's choices of dialogue. However these are far removed from the player's actions in the game world. Reacting to Aloy being compassionate, logical, or brutal, is something which adds a layer to the gameworld in how the player can interact with non-playable characters; however it does not alter the progression of the narrative, or affect the gameplay.

If Horizon: Zero Dawn provided some of this overworld response to the player's actions beyond marking an area as done and giving the player materials to craft better items, then much of the open world presentation of the game would be made more immersive. This immersion would be due to the depth provided in having a range of results available to the players actions, as opposed to a binarycompletion of objectives. Enabling for different groups to flourish, or having side effects to the extent to which alloy hunts and destroys predators would mean that the actions of the character would carry weight in the world.

Instead what is shown in Horizon: Zero Dawn is the pressence of an open world without any variation to the outcome. In other games the player's actions and decisions make an impact on the game world world and effect it's open nature showing it to be a dynamic system and not just a landscape to get from point A to point B.

Sunday, 16 July 2017

Torment Tides of Numeria

Torment Tides of Numeria is the reason people get into videogames, role playing games, fantasy, programming, you name it. Torment Tides of Numeria is a game that makes you want to go out and do something, to conquer worlds or at the very least shake it with your conviction. A would be god falling to earth, magic that's not magic, a host of dimensions and races that make the world seem larger than it is, a unique crisis system which enables for more than just combat. And a range of other little world building checkboxes within the overall presentation which hangs upon other elements of the game to form a unified fantastical experience.

There were divergent pathways, there were quests that flowed into other quests there were memorable characters and there were interesting dilemmas. I enjoyed Torment Tides of Numeria, just as much as I enjoyed Tyranny, or if we're harkening back to the inspiration for these videogames Planescape: Torment. The storyline follows many of the same beats as Planescape with the amnesic player-character, and their near mythical status as the person who cannot die. Torment, as opposed to Planescape, runs with this superpower and uses the fact that the player-character's near immortality is something which has been monopolised on in the past enabling for a god-worship of the player-character due to their inability to die and their mastery of the 'tides' a power that runs above the worlds themselves and affects dimensions. The player discovers tall of this through their playthrough of the videogame, choosing to return to their lofty godhood, or to again become humble in their endeavors to stop their powergrab/desire to live forever and come to terms with their mortal coil - so as to save all worlds from the disruption of the tides. Although this presentation gives the player an ability for self redemption (through their self sacrifice), as well as the ability to proceed with their 'I want to live forever' masterplan the impact of the end game choice does not appear to be as weighty as Planescape's. Although once again the player-character is dealing with the fate of the universe in comparison to their own life the impetus for living forever and atoning for that desire seems weaker than Planescape's self redemption, and then eternal damnation fighting the endless wars. The player-character although they can express guilt, does not explore what can change the nature of the man - instead the player-character proceeds to continue looking for the next objective and task without that impact of what they are and why they should change becoming apparent. Not that the game was a bad one at all, just the impact of the ending compared to Planescape meant that the resolution was not tied into what the player's character has done.

That all being said the companion character of Rhin made for a compelling narrative for the later half of the videogame. Rhin is an orphan thrust into the world of Numeria, who can later become a companion character and allow you to reuse cyphers (powerful spells); however as a child she is not very strong in a fight. And it's strange because the normalcy of having a child as a party member (who wasn't that useful originally) really grew on me as I was playing the videogame, to the extent that I kept her in the party because she didn't want to live out on the streets, and had a hard time dealing with different encounters. Eventually I learned how to play with Rhin as a companion character and used her to support my other characters, yet half way through my play I was offered a choice to release Rhin into an orphanage so that she could have a normal childhood (albeit in the future with a couple that she did not know). I initially refused based on the fact that Rhin did not seem comfortable with the arrangement, and that the whole thing felt as though I was abandoning the companion character as a nuisance, rather than actually trying to help her out. Later I was presented with a similar situation except instead of offloading Rhin to an orphanage, I was given the chance to return Rhin to her original home, which Rhin was a fan of. I was torn at this point because it was close to the end of the videogame, and I had leveled Rhin up to the point that she was contributing to the team. I actually didn't want to let her go. Eventually I relented and returned her to her own dimensional area, but for a while both narratively and gameplay wise I wanted to keep her on as a companion character.

So for that character of Rhin, and the crisis of doing the right thing vs being able to beat the game I was happy for the development of Torment Tides of Numeria. Apparently the whole situation with Rhin is largely optional and up to the player to complete as they wish, so it felt really nice to have finished the videogame with my own little contribution to my companion characters - I returned a girl back to her homeworld, how can that not be satisfying? And it wasn't something that I had to do but a nice self contained story that felt well told and also put pressure on me as a player and character to do the right thing vs. my own abilities (which is something that not a lot of videogames do). Planescape I think did this to a large extent with the ability for the player-character the 'Nameless One' to take damage or stunt skills in order to find more about themselves or the world, which was a good trade off in terms of a cost for knowledge.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/58824351/ITB_large.0.png)

.png)